Italy, Corte di Cassazione, Rights of same-sex couples, judgment n. 4184/12

Deciding bodies and decisions

Corte di Cassazione (Italian Court of Cassation)

Subject matter

Recognition of same-sex marriage officiated abroad, in a Member State that does not

allow same-sex marriages

allow same-sex marriages

Summary Facts Of The Case

A couple of Italian mentried to have their marriage officiated in the Netherlands- recognized in Italy, where same-sex marriage is not allowed. Accordingly, recognition had been denied on grounds of ordre public, and challenges in lower courts had been rejected for the same reason. Before the Supreme Court, the couple argued that such refusal was in breach, inter alia, of Italy’s non-discrimination commitments under EU law, in light of the ECHR’s standards of equal treatment. The Italian Supreme Court refused to raise a preliminary question on the interpretation of EU Charter Rights, alleging the absence of a link with EU law (as required by Art. 51(1) of the EU Charter).

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court expanded on the reasoning of the Italian Constitutional Court and of the ECtHR. In previous judgments, these had, respectively, granted constitutional coverage to same-sex unions (as ‘social groups’ under Art. 2 of the Constitution (cf. Corte costituzionale, judgment no. 138/2010 of 14 April 2010), and noticed that marriage is not necessarily a different same-sex affair (cf. ECtHR: Schalk and Kopf v Austria, Application no. 30141/04, judgment of 24 June 2010). On that occasion, the ECtHR had ultimately registered the lack of consensus across the Members of the Council of Europe, and accordingly found that the recognition of same-sex marriages is a matter of exclusive competence of the State, pursuant to the margin of appreciation doctrine. The Italian Supreme Court upheld the refusal to register the marriage in Italy, but held that there was no inherent problem of ordre public, in light of the ECtHR’s requirements and of the current state of public opinion. The refusal was rather grounded on the circumstance that same-sex marriage has no equivalent in Italian law and thus cannot be recognised for the purpose of acquiring legal effects. Being there no constitutional obstacle to that recognition, the Court concluded that the Parliament is free to pass a statute legalising same-sex marriages, and that in any event same-sex couples are provided, under the Constitution, the right to enjoy family life in a non-discriminatory way (quite apart from the legal recognition.

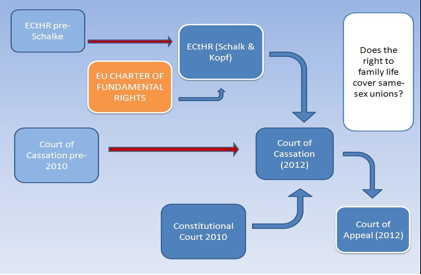

Diagram

Vertical internal interaction (Supreme Court - ECtHR)

Vertical external interaction (Supreme Court - Constitutional Court )

The Italian Supreme Court used the case-law of the ECtHR and of the national Constitutional Court in order to update its previous interpretation of a fundamental right, through consistent interpretation techniques. In particular, it relied on a judgment where the ECtHR provided a right of the ECHR with a wider meaning than what its wording would suggest, using the EU Charter. At the same time, the Strasbourg Court left some margin of appreciation to the High Contracting Parties. Following the judgment of the Supreme Court, national courts are presented with a full set of authorities to draw inspiration from: Constitutional Court, Supreme Court, ECtHR and EU law.

Impact on Jurisprudence

Shortly after the decision by the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal of Milan, Labour Section (judgment no. 7176 of 31 August 2012) made explicit reference to all decisions recalled above (of the Italian Supreme Court, the Constitutional Court and the ECtHR) to conclude that rights vested in unmarried couples (cohabitants more uxorio) are extended to same-sex couples. The Court noted that ‘In the current socio-political reality the concept of cohabitation cannot be limited tocouples of persons of different sex, as long as there is a form of stable life-sharing communion without marriage, which takes the shape of a family unit based on solidarity and mutual support. Homosexual unions can also qualify, and the widespread social sentiment recognizes them the right to fully enjoy family life. In its order of 3-9 April 2014, the Tribunal of Grosseto referred to the part of the judgment where the Supreme Court, quoting Shalk and Kopf, affirmed that recognition of same-sex marriages is not in contrast with the ordre public. The order is the first one requiring the competent State official to transcript in the civil registry the marriage that the applicants – a couple of men – celebrated in New York (the original text of the order and a comment can be found here: http://www.sidi-isil.org/sidiblog/?p

Sources - ECHR

- Art. 8 (Right to respect

for private and family life); - Art. 12 (right to marry);

- Art. 14 (non-discrimination)

Sources - CJEU Case Law

none

Sources - ECtHR Case Law

- Schalk and Kopf v Austria, Application no. 30141/04, judgment of 24 June

2010, (http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/sites/eng/pages/search.aspx?i=001-99605

Sources - Internal or external national courts case law

- Corte costituzionale, judgment no. 138/2010 of 14 April 2010, (http://www.cortecostituzionale.it/actionSchedaPronuncia.do anno=2010&numero=138

Comments

1. Comparative reasoning and consistent interpretation techniques led to a new interpretation of the constitutional principle of equality under the ECHR.

The ECtHR has interpreted Art. 12 ECHR in light of Art. 9 of the EU Charter. The open intention of this operation was to extend the scope of the right to family life. This comparative technique led to the declaration that same-sex marriage is, if not a right proper, a lawful option under the ECHR.

The Italian Supreme Court, recalling expressly its duties of consistent interpretation vis-à-vis ECtHR’s case-law and EU law, has overtly modified a long-established interpretation of a fundamental right, providing a new reading to the constitutional provision on non-discrimination (Art. 3), looking at the ECtHR’s use of Art. 14 and 8 of the ECHR.

2. Comparative reasoning /Spill-over effect?. Indirect judicial interaction between the Constitutional Courts

Although the Italian Supreme Court did not quote any (national) foreigner precedents, it was plausibly aware of the rulings that its foreign colleagues had been issuing in the previous years. For instance, in 2011 the German Federal Constitutional Court declared the discriminatory effect of the domestic rule preventing two people of different sex from registering their civil partnership when one of them was a transgender who had not undergone surgery. Even though they could perceive themselves as a same-sex couple, the unconstitutional regulation previously in force made only marriage available to them, and reserved civil partnership to same sex-couples (Federal Constitutional Court of Germany, judgment of 11 January 2011, 1 BvR 3295/07). Before that, on 21 July 2010, the German Constitutional Court declared the unconstitutionality of domestic regulations that imposed a higher fiscal burden on civil partnerships, compared to married couples (Federal Constitutional Court of Germany, order of 21 July 2010 – 1 BvR 611/07, 1 BvR 2464/07). The Bundesverfassungsgericht recalled, inter alia, that differential treatment must be based on objective criteria of difference that make two situations not comparable, and cannot be justified only based on a generic reference to the State’s duty to protect marriage and family life. On an issue closer to the one ruled by the Italian Supreme and Constitutional Courts, see the decision of the Portuguese Constitutional Court of 9 July 2009, ruling that the Constitution does not require (nor prevents) recognition of same-sex relationships (Portuguese Constitutional Court, Acórdão no. 359/2009 of 9 July 2009, with a dissent of two judges, who favored the idea of a constitutional right to marriage for same-sex couples). On 28 January 2011, instead the French Conseil Constitutionnel held that the ban on same-sex marriage in France was not unconstitutional (Décision n° 2010-92 QPC du 28 janvier 2011, M.me Corinne et autres) since, inter alia, it did not encroach upon the fundamental right to enjoy family life granted to everyone, regardless of the right to marry.

3. Impact on the national case-law/jurisprudence

After the judgment of the Italian Supreme Court of 2012, Italian judges can safely refer to the obiter dicta of the Supreme Court, and investigate whether certain specific same-sex couples’ rights have a EU-law dimension (for instance, on the freedom of movement). If so, that link can be used to apply the EU Charter directly, or to raise a preliminary question to the CJEU, in the attempt to instigate an evolutionary trend. Some tribunals have already found that the provision of Art. 2(2)(a) of the Citizens’ Directive 2004/38, which includes the citizen’s “spouse” among the members of his family (who enjoy rights of residence under Art. 7) cannot be interpreted solely to include different-sex spouses, as long as there is a valid marriage celebrated in one Member State (cf. see Italian Supreme Court, Criminal section (I), judgment no. 1328, 19 January 2011. Also see Tribunal Reggio Emilia, judgment no. 1401, 13 February 2012, available at http://www.tuttostranieri.org/le-norme/sentenze/383-sentenza-del-13-febbraio-2012-dal-tribunale-di-reggio-emilia

Relevant Judicial Dialogue Techniques

Project implemented with financial support of the Fundamental Rights & Citizenship Programme of the European Union

© European University Institute 2019

Villa Schifanoia - Via Boccaccio 121, I-50133 Firenze - Italy