United Kingdom, The Supreme Court, R (on the application of EM, EH, AE and MA v Secretary of State for the Home Department), Judgement of 19 February 2014

Deciding bodies and decisions

UK Supreme Court, Judgement of 19 February 2014

Area of law

EU asylum law

Subject matter

Asylum seeker application - transfer to the Member State of first entry under Dublin II system rules - systemic deficiency test - inhumane and degrading treatment

Summary Facts Of The Case

The applicants, EM, EH, AE, MA, Iranian and Eritrean nationals, contested the return decision of the UK Secretary of State for the Home Department concerning their return to Italy. The applicants claimed that a transfer to Italy, the first country of entry according to the Dublin system, would go against their basic human rights and would therefore not be consistent with the prohibition of inhumaine and degrading treatment under Article 3 ECHR and Article 4 of the EU Charter.

Relation to the scope of the Charter

The case falls within the scope of the Charter as the UK national authorities are implementing EU law for the purpose of Article 51(1) of the Charter. The EU law connecting element is Article 3(2) of Dublin II Regulation (Regulation 343/2003), which allows Memebr State to refuse the return of an asylum seeker in the state of first arrival.

Relation between the Charter and EHCR

The UK Supreme Court reconciled the potentially conflictual interpretation of the two European supranational courts on the matter, by interpreting the N.S. and others preliminary ruling in light of established jurisprudence of the ECtHR, such as the Soering case. The UK Supreme Court held that, under EU law, Member States have to comply with the ECHR, and also the 1998 Human Rights Act which requires the Home Secretary to conform to the ECHR. The UK Supreme Court established that the legal test to be followed when determining whether particular violations of human rights amount to legitimate grounds for limiting mutual trust should be the ECtHR Soering test coupled with the M.S.S and N.S. thresholds. Thereby, both operational, systemic failures in the national asylum systems and individual risks of being exposed to treatment contrary to Article 3 ECHR and Article 4 EU Charter should be considered as legitimate thresholds for the limitation of the principle of mutual trust

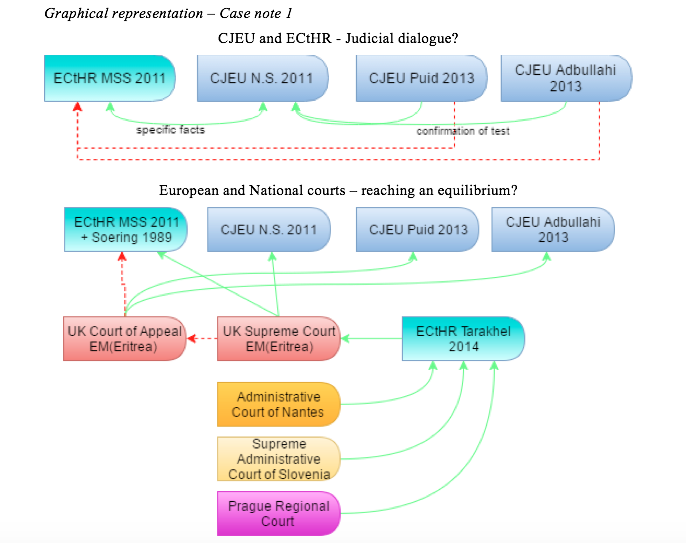

Diagram

Vertical (UK Court of Appeal – UK Supreme Court)

Vertical (UK Court of Appeal and Supreme Court – CJEU and ECtHR)

Horizontal (CJEU – ECtHR)

Through consistent interpretation technique, national courts engaged in vertical judicial dialogue with the CJEU and ECtHR standard of protection on prohibition of inhumane or degrading treatment in cases involving transfers of asylum seekers under EU Dublin system

Impact on Jurisprudence

The UK Supreme Court approach was echoed by other national judgments on Dublin transfers, including under the revised Dublin III Regulation transfers.

As regards Dublin transfers to Italy, the Administrative Court of Nantes quashed a decision of a Dublin transfer to Italy based on the administration failure to carry out “a full and rigorous examination of the consequences of the applicant’s transfer in Italy”, and in particular of the existence of the N.S. conditions of “substantial grounds for believing that there are systemic flaws in the [Italian] asylum procedure and in the reception conditions”.

Similarly, the Supreme Administrative Court of Slovenia required the administration to carry out a rigorous examination of the circumstances regarding accommodation in Italy when an applicant for international protection claimed a threat of ill treatment and provided supporting evidence and reports.

The Prague Regional Court quashed the administrative decision of returning an asylum seeker in Bulgaria based on the absence of an assessment run by the administration of whether the Bulgarian asylum system enables an adequate health and other necessary measures.

Sources - EU and national law

- Article 4 EU Charter

- Article 51 EU Charter

Sources - ECHR

- Article 3 ECHR

Sources - CJEU Case Law

- Case C-411/10, N.S. and others, ECLI:EU:C:2011:865

- Case C-394/12, Shamso Abdullahi v Bundesasylamt, ECLI:EU:C:2013:813

- Case C-4/11, Puid, EU:C:2013:740

Sources - ECtHR Case Law

- MSS v Belgium and Greece, Application no. 30696/09, 21 January 2011

- Tarakhel v Switzerland, Application no. 29217/12, 4 November 2014

- Soering v UK, Application no. 14038/88, 07 July 1989

Comments

The prohibition of inhumane and degrading treatment lies at the heart of the controversy surrounding the operation of the Dublin System for determining the responsible Member State for asylum applications and for transferring individuals accordingly. Prompted by the ECtHR’s decision in MSS v Belgium, the Court of Justice adopted the ‘systemic deficiencies’ test in NS finding that under Article 4 of the EU Charter a Member State is obliged to suspend a transfer to a Member State under the Dublin System if ‘it cannot be unaware that systemic deficiencies in the asylum procedure and in the reception conditions of asylum seekers in [the receiving] Member State amount to substantial grounds for believing that the asylum seeker would face a real risk of being subjected to inhumane or degrading treatment within Article 4 of the Charter.’ The CJEU confirmed the ‘systemic deficiencies’ test in subsequent jurisprudence on Dublin transfers to Greece (Puid, Abdullahi). Whether this obligation corresponds to the ECHR’s jurisprudence under Article 3 ECHR is open to question and there remains a certain tension between the two Courts on this issue. For instance, the 2014 Tarakhel judgment of the ECtHR clarifies that ‘in the case of “Dublin” returns, the presumption that a Contracting State which is also the “receiving” country will comply with Article 3 of the Convention can therefore validly be rebutted where “substantial grounds have been shown for believing” that the person whose return is being ordered faces a “real risk” of being subjected to treatment contrary to that provision in the receiving country.’ (para. 104). The ECtHR requires that the N.S. ‘systemic deficiencies’ test should not be the sole test to establish violations of Article 3 ECHR, but also an individual examination of the case, in particular a “thorough and individualised examination of the situation of the person concerned" in the state of destination might also lead to find a violation of Article 3 ECHR (Tarakhel v Switzerland, paras. 101 and 121).

National courts faced with the practical challenge of reconciling two potentially conflicting obligations have also weighed in on the debate, with notable contributions from the UK courts, similar to the one presented in this case note.

Relevant Judicial Dialogue Techniques

Project implemented with financial support of the Fundamental Rights & Citizenship Programme of the European Union

© European University Institute 2019

Villa Schifanoia - Via Boccaccio 121, I-50133 Firenze - Italy