European Union, CJEU, Abdida, Judgement of 18 December 2014

CJEU C?239/14, Tall, 17 December 2015, ECLI:EU:C:2015:824

Belgium, Council of Alien Law Litigation, n. 155 216, 23 octobre 2015,

Belgium, Constitutional Court, n. 1/2014, 16 January 2014

Mr Abdida was recognised a right of residence based on medical grounds and received social assistance. Subsequently, his application for leave to reside was rejected on the ground that his country of origin has adequate medical infrastructure, he was granted emergency medical care, but withdraw social assistance.

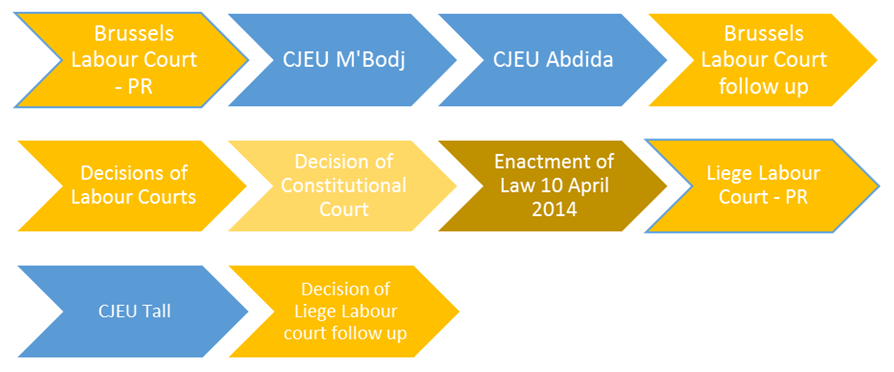

The Brussels Labor Court asked the CJEU whether the asylum related directives or the Charter require the Member State to provide for a ‘remedy with suspensive effect in respect of the administrative decision refusing leave to remain and/or subsidiary protection, and ordering the person concerned to leave the territory of that State’, and medical and social assistance pending the examination of the appeal against a refusal of a permit to stay for medical reasons.

First of all, ‘a third country national must be afforded an effective remedy to appeal against or seek review of a decision ordering his return.’ (para. 43)

Secondly, there has to be an ‘authority or body with power to adjudicate on such an appeal’ which ‘may temporarily suspend enforcement of the return decision that is being challenged, unless a temporary suspension is already applicable under national legislation.’

Although the CJEU interpreted that Article 13 of the Return Directive does not require that an appeal against a return decision has automatic suspensive appeal, it also held that these provisions need to be interpreted ‘in a manner that is consistent with Article 47 of the Charter, which constitutes a reaffirmation of the principle of effective judicial protection (see, to that effect, judgments in Unibet, C 432/05, EU:C:2007:163, paragraph 37, and Agrokonsulting, C 93/12, EU:C:2013:432, paragraph 59)’ (para. 45) Additionally Article 13 of the Return Directive needs to be interpreted in a manner consistent also with Article 19(2) of the Charter. According to Article 52(3) CFR, the requirements set out under Article 19(2) CFR were interpreted by the CJEU in light of the jurisprudence developed by the ECtHR regarding prohibition of expulsion under Article 3 ECHR in medical cases (N. v. the United Kingdom [GC], no. 26565/05, § 42, ECHR 2008). The CJEU found that the ECtHR recognised an ‘entitlement to remain in the territory of a State in order to continue to benefit from medical, social or other forms of assistance and services provided by that State, [when] a decision to remove a foreign national suffering from a serious physical or mental illness to a country where the facilities for the treatment of the illness are inferior to those available in that State.’ (para. 47)

These ECtHR derived requirements would translate under the EU legal order in an obligation of refusing enforcement of a return decision entailing the removal of a third country national suffering from a serious illness to a country in which appropriate treatment is not available’(Article 5 of Directive 2008/115).

‘The European Court of Human Rights has held that, when a State decides to return a foreign national to a country where, there are substantial grounds for believing, he will be exposed to a real risk of ill-treatment contrary to Article 3 ECHR, the right to an effective remedy provided for in Article 13 ECHR requires that a remedy enabling suspension of enforcement of the measure authorising removal should, ipso jure, be available to the persons concerned (see, inter alia, European Court of Human Rights, judgments in Gebremedhin [Gaberamadhien] v. France, no. 25389/05, § 67, ECHR 2007-II, and Hirsi Jamaa and Others v. Italy [GC], no. 27765/09, § 200, ECHR 2012). 53 It follows from the foregoing that Articles 5 and 13 of Directive 2008/115, taken in conjunction with Articles 19(2) and 47 of the Charter, must be interpreted as precluding national legislation which does not make provision for a remedy with suspensive effect in respect of a return decision whose enforcement may expose the third country national concerned to a serious risk of grave and irreversible deterioration in his state of health.

After the adoption of ‘Law of 10 April 2014’, but before its entry into force of 21st of May 2014, another Belgian Labour Court addressed preliminary questions to the CJEU on the effectiveness of the remedy of the appeal in multiple asylum application proceedings, leading to the CJEU decision in Tall case.

Article 19(2) EU Charter

- Article 3 ECHR

- Article 13 ECHR

- CJEU, C-542/13, M'Bodj, ECLI:EU:C:2014:2452

Relevant Judicial Dialogue Techniques

Other Databases