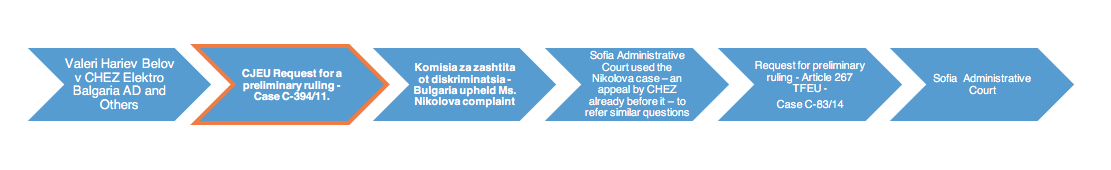

European Union, CJEU, C-83/14, CHEZ, Judgment of 16 July 2015

In December 2008, Ms Nikolova lodged an application with the Bulgarian Commission for Protection from Discrimination (KZD) in which she contended that the reason for the practice at issue was that most of the inhabitants of the ‘Gizdova mahala’ district were of Roma origin, and that she was accordingly suffering direct discrimination on the grounds of nationality (‘narodnost’). She complained in particular that she was unable to check her electricity meter for the purpose of monitoring her consumption and making sure that the bills sent to her, which in her view overcharged her, were correct.

On 6 April 2010, the KZD issued a decision concluding that the practice at issue constituted prohibited indirect indiscrimination on the grounds of nationality.

That decision was annulled by judgment of the Varhoven administrativen sad (Supreme Administrative Court) of 19 May 2011, in particular on the ground that the KZD had not indicated the other nationality in relation to the holders of which Ms Nikolova had suffered discrimination. The case was referred back to the KZD.

On 30 May 2012, the KZD adopted a fresh decision finding that CHEZ RB had discriminated directly against Ms Nikolova on the grounds of her ‘personal situation’, by placing her, on account of where her business was located, in a disadvantageous position compared with CHEZ RB’s other customers whose meters were in accessible locations.

5. CHEZ RB challenged that decision before the Administrativen sad Sofia-grad (Administrative Court, Sofia). In its order for reference, that court finds, as a preliminary point, that the RED implements the general principle prohibiting discrimination based on race or ethnic origin [correctly: racial or ethnic origin!] which is in particular enshrined in Article 21 of the Charter and that the situation at issue in the main proceedings falls within the RED’s material scope. The referring court not doubting that EU law is applicable, does not refer a question for a preliminary ruling in that regard, while observing that the Court of Justice will, in any event, be called upon to assess this matter before ruling on the questions referred.

According to the referring court, the protected ground must be seen in relation to the common Roma ‘ethnic origin’ of most of the inhabitants of the ‘Gizdova mahala' district, while the Roma community constitutes an ethnic community, which is recognized as an ethnic minority in Bulgaria. [The question appears to relate to whether groups of citizens perceived as a monolithic collective and not as individuals are protected under the RED.]

The form of discrimination needs to be clarified. Even though the referring court is inclined to agree with the KZD’s conclusion that the practice at issue gives rise to direct discrimination, it notes that, in her Opinion delivered in Belov (C-394/11, EU:C:2012:585, point 99), Advocate General Kokott concluded that a practice such as the practice at issue amounted prima facie to indirect discrimination. It also observes that in similar cases the Varhoven administrativen sad concluded that there was not any direct or indirect discrimination on the grounds of ethnic origin. In the event the practice at issue amounted to indirect discrimination, the referring court doubts that it can be regarded as objectively justified, appropriate and necessary within the meaning of that provision. It points out in particular the lack of evidence in this regard.

The questions referred to the CJEU concern

- the meaning of “ethnic origin” in the Racial Equality Directive and the Charter,

- the permissibility of comparison between districts on the grounds of ethnic origin

- whether less favorable treatment has been meted out in the case

- the applicability of the concept of direct and indirect discrimination to the present case in light of the phrase used to define direct (‘less favorable treatment’) and indirect discrimination (‘in a particularly less favourable position’) under Article 2(2) Racial Equality Directive. Does the latter cover only serious, obvious and particularly significant cases of unequal treatment?

The case constitutes the first substantive judgment on anti-Roma discrimination delivered by the CJEU: the threshold of protection is very high and may not be followed in cases dealing with other grounds (McCrudden).

The CJEU returned the case to the Sofia Administrative Court for it to resolve. The CJEU analysis is geared towards finding direct discrimination. This is important, because previously, many cases failed before Bulgarian courts. The case is still pending.

- Racial equality Directive 2000/43/EC

- Energy Efficiency Directive 2006/32/EC

- Common internal market in electricity Directive 2009/72/EC

- National law on non-discrimination (ZZD)

- National law on energy (ZE)

Article 21 is attributed a pivotal role in answering question 1 by legitimating a purposeful and wide interpretation of the personal scope of the Racial Equality Directive. The directive “is merely an expression, within the area under consideration, of the principle of equality, which is one of the general principles of EU law, as recognised in Article 21 of the Charter, the scope of that directive cannot be defined restrictively (judgment in Runevi?-Vardyn and Wardyn, C391/09, EU:C:2011:291, paragraph 43)” (para 42 of CJEU).

The concept of ‘discrimination on the grounds of ethnic origin’, for the purpose of the Racial Equality Directive, must be interpreted as being intended to apply to persons who have a certain ethnic origin or those who, without possessing that origin, suffer, together with the former, from the less favourable treatment or particular disadvantage – the protection against discrimination on grounds of racial or ethnic origin which the directive is designed to guarantee is to benefit ‘all’ persons. (para 57).

According to the CJEU (para 58) this results from the wording of Article 19 TFEU and of the principle of non-discrimination on grounds of race and ethnic origin enshrined in Article 21 of the Charter, to which the directive gives specific expression in the substantive fields that it covers (see judgment in Runevi?-Vardyn and Wardyn, C391/09, EU:C:2011:291, paragraph 43, and, by analogy, judgment in Felber, C529/13, EU:C:2015:20, paragraphs 15 and 16). The Court also invites to by analogy, look into the judgment in Coleman, C303/06, EU:C:2008:415, paragraph 38).

Article 21 frames the answers to Questions 2 to 4 as “Directive 2000/43 gives specific expression, in its field of application, to the principle of non-discrimination on grounds of race and ethnic origin which is enshrined in Article 21 of the Charter” (para 72). Article 21 is used to support a higher level of protection against the practice in the case. In answering questions 2 to 4 the CJEU establishes that CHEZ RB’s practices are “offensive and stigmatising” (para 84, 87, 108) and constitute direct discrimination (76) but this is a matter which is for the referring court to determine (para 91).

According to the CJEU the comparator at stake are other urban districts (provided with electricity by CHEZ) and not districts with the same levels of interference with the meters: “in principle, all final consumers of electricity who are supplied by the same distributor within an urban area must, irrespective of the district in which they reside, be regarded as being, in relation to that distributor, in a comparable situation” (para 90).

The CJEU empowers the national courts by stating that it is for “the referring court to take account of all the circumstances surrounding the practice at issue” (...) “and to ensure that a refusal of disclosure by the respondent, here CHEZ RB, in the context of establishing such facts is not liable to compromise the achievement of the objectives pursued by Directive 2000/43 (see, to this effect, judgment in Meister, C415/10, EU:C:2012:217, paragraph 42)”. The CJEU stresses that CHEZ RB asserted that in its view the “damage and unlawful connections are perpetrated mainly by Bulgarian nationals of Roma origin”. Such assertions suggest that the practice at issue is based on “ethnic stereotypes or prejudices”. Plus, notwithstanding requests to this effect from the referring court in respect of the burden of proof, the CJEU highlights that CHEZ RB affirmed that they are “common knowledge”. Bulgarian citizens of Roma origin are being considered “as a whole” (...) “potential perpetrators”. The Court recalls that such a perception may also be relevant for the overall assessment of the practice at issue (see, by analogy, judgment in Asocia?ia Accept, C81/12, EU:C:2013:275, paragraph 51).

To answer Questions 5 to 9 the CJEU rules that a practice, such as that at issue in the main proceedings, does not amount to direct discrimination within the meaning of Article 2(2)(a) of the directive, is then, in principle, liable to constitute an apparently “neutral practice” putting persons of a given ethnic origin at a particular disadvantage compared with other persons and therefore constituting indirect discrimination.

The concept be understood not as designating a practice whose neutrality is particularly ‘obvious’ or neutral ‘at first glance’, but as being neutral ‘ostensibly’. It is the Court’s settled case-law that indirect discrimination may stem from a measure which, albeit formulated in neutral terms, that is to say, by reference to other criteria not related to the protected characteristic, leads, however, to the result that particularly persons possessing that characteristic are put at a disadvantage (see to this effect, in particular, judgment in Z., C-363/12, EU:C:2014:159, paragraph 53 and the case-law cited). If it is apparent that a measure which gives rise to a difference in treatment has been introduced for reasons relating to racial or ethnic origin, that measure must be classified as ‘direct discrimination’ within the meaning of Article 2(2)(a) of Directive 2000/43.

According to the Court’s case law on indirect discrimination, it is liable to arise when a national measure, albeit formulated in neutral terms, works to the disadvantage of far more persons possessing the protected characteristic than persons not possessing it (see in particular, to this effect, judgments in Z., C-363/12, EU:C:2014:159, paragraph 53 and the case-law cited, and Cachaldora Fernández, C-527/13, EU:C:2015:215, paragraph 28 and the case-law cited). No particular degree of seriousness is required so far as concerns the particular disadvantage referred to in the RED.

Held: Article 2(2)(b) of Directive 2000/43 must be interpreted as meaning that:

that provision precludes a national provision according to which, in order for there to be indirect discrimination on the grounds of racial or ethnic origin, the particular disadvantage must have been brought about for reasons of racial or ethnic origin;

the concept of an ‘apparently neutral’ provision, criterion or practice as referred to in that provision means a provision, criterion or practice which is worded or applied, ostensibly, in a neutral manner, that is to say, having regard to factors different from and not equivalent to the protected characteristic;

the concept of ‘particular disadvantage’ within the meaning of that provision does not refer to serious, obvious or particularly significant cases of inequality, but denotes that it is particularly persons of a given racial or ethnic origin who are at a assuming that a measure, such as that described in paragraph 1 of this operative part, does not amount to direct discrimination within the meaning of Article 2(2)(a) of the directive, such a measure is then, in principle, liable to constitute an apparently neutral practice putting persons of a given ethnic origin at a particular disadvantage compared with other persons, within the meaning of Article 2(2)(b).

On question 10 and on indirect discrimination, the CJEU ruled that any measure disadvantaging a Roma majority district which is not applied to non-Roma majority districts needs to be objectively justified. Combating of fraud and criminality constitute legitimate aims recognised by EU law (see Placanica and Others, C?338/04, C?359/04 and C?360/04, EU:C:2007:133, paragraphs 46 and 55) but objective justification must be interpreted strictly.

The practice is said to be designed both to prevent fraud and abuse and to protect individuals against the risks to their life and health to which such conduct gives rise, as well as to ensure the quality and security of electricity distribution in the interest of all users.

However, the company has the task at the very least of establishing objectively, first, the actual existence and extent of that unlawful conduct and, second, in the light of the fact that some 25 years have since elapsed, the precise reasons for which there is, as matters currently stand, a major risk in the district concerned that such damage and unlawful connections to meters will continue. CHEZ RB cannot merely contend that such conduct and risks are ‘common knowledge’, as it seems to have done before the referring court.

In case CHEZ RB is able to establish that the practice at issue objectively pursues the legitimate aims relied upon by it, it will also be necessary to establish, as Article 2(2)(b) of Directive 2000/43 requires, that that practice constitutes an appropriate and necessary means for the purpose of achieving those aims. Would other appropriate and less restrictive measures not enable the problems encountered to be resolved? The KZD submitted in its observations that other electricity distribution companies have given up the practice at issue, giving preference to other techniques for the purpose of combating damage and tampering, and have restored the electricity meters in the districts concerned to a normal height.

It is for the referring court to determine whether other appropriate and less restrictive measures thus exist for the purpose of achieving the aims invoked by CHEZ RB and, if that is so, to hold that the practice at issue cannot be regarded as necessary within the meaning of Article 2(2)(b) of Directive 2000/43.

Furthermore, assuming that no other measure as effective as the practice at issue can be identified, the referring court will also have to determine whether the disadvantages caused by the practice at issue are disproportionate to the aims pursued and whether that practice unduly prejudices the legitimate interests of the persons inhabiting the district concerned (see to this effect, in particular, judgments in Ingeniørforeningen i Danmark, C-499/08, EU:C:2010:600, paragraphs 32 and 47, and Nelson and Others, C-581/10 and C-629/10, EU:C:2012:657, paragraph 76 et seq.).

The referring court will, first, have to pay regard to the legitimate interest of the final consumers of electricity in having access to the supply of electricity in conditions which do not have an offensive or stigmatising effect.

It will also be incumbent upon it to take into consideration the binding, widespread and long- standing nature of the practice at issue. In its assessment, the referring court will, finally, have to take account of the legitimate interest of the final consumers inhabiting the district concerned in being able to check and monitor their electricity consumption effectively and regularly.

Although it seems that it necessarily follows from the taking into account of all the foregoing criteria that the practice at issue cannot be justified under the RED, in the context of proceedings concerning a preliminary reference made on the basis of Article 267 TFEU it is for the referring court to carry out the final assessments which are necessary in that regard.

The Court held that a measure such as that at issue in the main proceedings would be capable of being objectively justified by the intention to ensure the security of the electricity transmission network and the due recording of electricity consumption only if that practice did not go beyond what is appropriate and necessary to achieve those legitimate aims and the disadvantages caused were not disproportionate to the objectives thereby pursued. That is not so if it is found, a matter which is for the referring court to determine, either that other appropriate and less restrictive means enabling those aims to be achieved exist or, in the absence of such other means, that that practice prejudices excessively the legitimate interest of the final consumers of electricity inhabiting the district concerned, mainly lived in by inhabitants of Roma origin, in having access to the supply of electricity in conditions which are not of an offensive or stigmatising nature and which enable them to monitor their electricity consumption regularly.

Relevant Judicial Dialogue Techniques