European Union, CJEU, A, B and C, Judgement of 4 December 2014

- Court of Justice of the EU, Joined Cases C?148/13 to C?150/13, Judgement of 4 December 2014

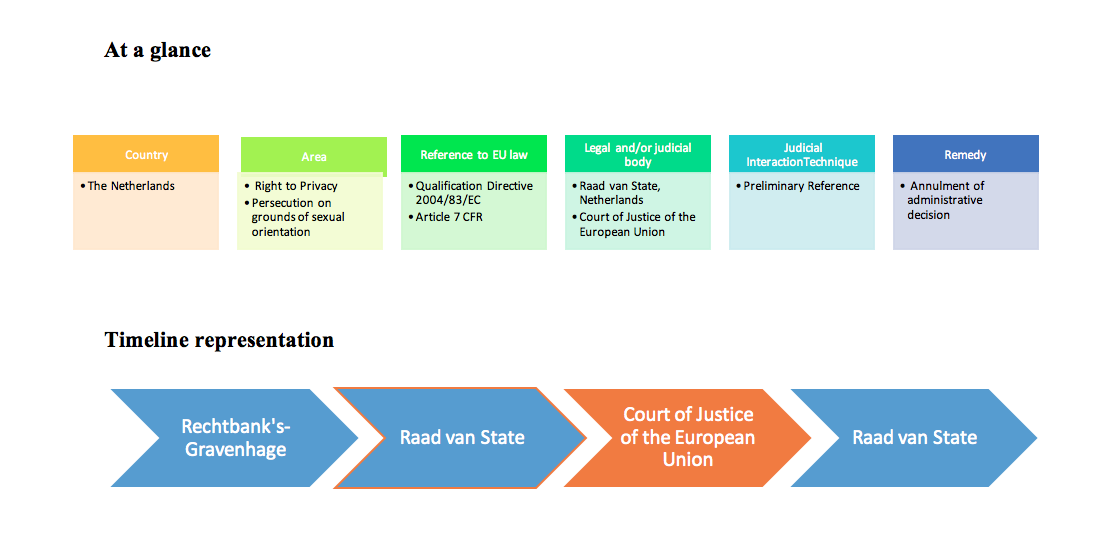

- Dutch Council of States, Applications 201208550/1/V2, 201110141/1/V2, 201210441/1/V2 (Afdeling bestuursrechtspraak van de Raad van State)

- Asylum and immigration

Asylum application – persecution on the grounds of sexual orientation – credibly assessment – permissible measures in assessing credibility - Article 7 Charter– right to privacy

All three applicants made applications for asylum based on persecution as homosexuals in their countries of origin. All three applications were rejected on grounds of credibility as to the true sexual orientation of the applicants. One applicant had failed to indicate his sexual orientation on his initial application. Others gave statements that were vague and inconsistent. Upon rejection, one applicant provided videos of him engaging in sex acts and another offered to undergo medical examination in order to ‘prove’ his sexual orientation. The referring Court had concerns regarding the nature of questioning and proof and the compatibility of assessment of a claim regarding the sexual orientation of an applicant with the requirements of Articles 1 (human dignity) and 7 (privacy) of the Charter and therefore referred the matter to the Court of Justice having regard to Article 4 of the Qualification Directive and the Charter.

Reasoning of the CJEU:

The Court of Justice held that assessments of application for asylum, including credibility assessments, must be conducted in compliance with Charter rights and in particular Article 7 CFR. While the details of asylum application procedures are generally a matter for national law, a number of conditions flow from Union law. The assessment of any application should be conducted in cooperation with the applicant and it is for the applicant to advance any particular claims including regarding sexual orientation. Furthermore, assessments must be conducted in compliance with the Charter, in particular Article 7 CFR on the right to privacy, and authorities may be required to modify their procedures in order to ensure compliance. Account should also be taken of Article 4(5) of the Qualification Directive detailing circumstances where documentary evidence may not be required, the authorities being permitted to rely on the statements of the applicants.

In relation to the specific situation of individuals claiming a particular sexual orientation, the Court outlined the limitations that may exist on the type of questioning and the assessment of this credibility. Firstly, it held that questioning based on ‘stereotypical’ notions may constitute a starting point, but only a starting point for an assessment. To hold otherwise and in particular reject an application based solely on the fact that an applicant is unaware of certain organisations would be contrary to the need to conduct an individual assessment, having regard to the specific circumstances of the applicant. Secondly, it held that detailed questions regarding sex acts would violate Article 7 CFR. Thirdly, it found that authorities cannot accept videos of sex acts, the performance of sex acts and of medical ‘tests’ regarding sexual orientation. Aside from the questionable probative value of such evidence, accepting it would violate the applicant’s human dignity under Article 1 CFR. Moreover, it would encourage others to submit similar evidence leading to a de facto requirement of such evidence. Finally, it found the fact of non-disclosure of sexual orientation earlier in the application process would not be fatal to credibility, having regard to the sensitivity of the subject matter.

- Article 7 – right to private and family life

Article 7 of the Charter and in particular the right to privacy limits the form of questions that could be asked and the types of proof that could be requested when assessing the credibility of a claim of sexual orientation.

The initial administrative decisions refusing asylum status were annulled.

The national court sought to clarify whether the manner in which national authorities assess the credibility of an alleged sexual orientation is compatible with the Qualifications Directive and the Charter of Fundamental Rights.

The initial administrative decisions refusing asylum status were annulled.

The Raad van State held that in general, the credibility assessment as conducted by the competent Dutch authorities was in line with the judgment of the CJEU and thus with EU law. The authorities do not ask questions about sexual activities of the foreign national and do not take into account any evidence such as films.

However, the Raad van State also held that, whereas the CJEU ruling gives a general framework within which the competent authorities of the Member States carry out the actual assessment, the Dutch authorities had failed to show how this assessment was carried out in individual cases. It was not only relevant to know what the authorities did not do or ask, but also what questions they did ask, how the answers to these questions were weighed and how the statements that lacked credibility concerning the problems the foreign national had already faced because of his alleged sexual orientation influenced the credibility of the claim of sexual orientation as such. Because all this was insufficiently clear, the administrative courts were not able to effectively rule on the credibility assessment in a given individual case. The decisions in the cases before the court were therefore annulled due to insufficient grounds for their decision being provided by the authorities.

Suggested Case(s)

Relevant Judicial Dialogue Techniques