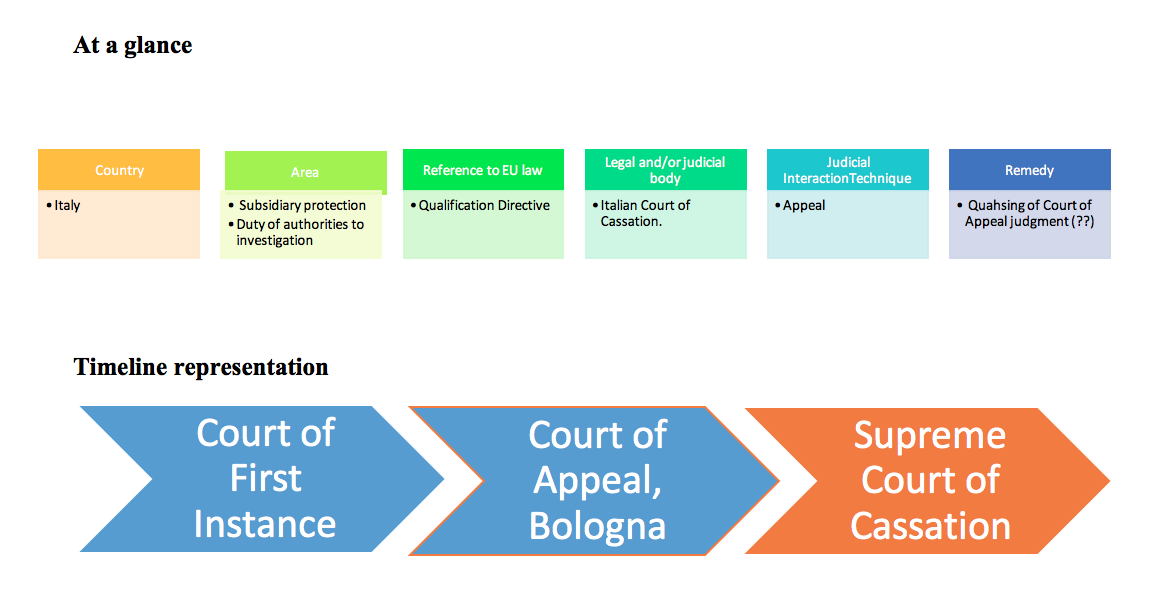

Italy, Supreme Court of Cassation, Iyan v Minister for Internal Affairs and Ors,

Right to asylum – Subsidiary protection – Art 2 ECHR – Art 3 ECHR – Art 18 CFR– Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees –UNCHR Guidelines on International Protection regarding Religion-Based Refugee Claims of 28 April 2004

The applicant, a Nigerian national, made an application for subsidiary protection in Italy. In it he alleged a threat to his life as a result of a succession dispute in his extended family following the death of his father that had already claimed the life of his wife. He did not submit any information in relation to the general security situation in Nigeria. He was granted subsidiary protection by the Court of First Instance. This however was reversed on appeal before the Court of Appeal of Bologna. The Court of Appeal found that the applicant had not established a direct link between the presence of high levels of indiscriminate violence in his country of origin and his own particular situation and the threat he faced. Accordingly he did not qualify for subsidiary protection. The applicant appealed this judgment before the Supreme Court of Cassation arguing that the Court of Appeal had rejected his claim based on the fact that he did not submit information regarding the general security in his country of origin and that there was a duty on the national authorities to take such facts into account when assessing an application for subsidiary protection.

- Legal issues

Whether the applicant was obliged to submit information regarding the general security situation in his country of origin or whether this information could be taken into account by judicial authorities on their own motion[SC1] .

The Supreme Court of Cassation reversed the judgment of the Court of Appeal of Bologna finding that the authorities are under a duty to take into account general information regarding the country of origin and the applicant.

It found that while the applicant has a general duty to submit as soon as possible all elements necessary to substantiate his claim, this does not entail an obligation to substantiate the specific grounds which make him eligible for protection; rather it is the duty of the judicial authorities to make the assessment of qualification for subsidiary protection. In doing so the judicial authority is obliged to take into account ‘all relevant facts as they relate to the country of origin at the time of taking a decision on the application’.[1] These relevant facts may in turn be used in assessing the credibility of the applicant. Finally, the Court cited the Court of Justice judgments of Elgafaji[2]and Diakitè[3] noting that “the more the applicant is able to show that he is specifically affected by reason of factors particular to his personal circumstances, the lower the level of indiscriminate violence required for him to be eligible for subsidiary protection” and vice versa.

- Outcome

In applying these findings to the present case the Supreme Court found that the credibility of the applicant had been established and that taking into account the general security situation in Nigeria, the persistent conflict between tribes and the general lack of control by the authorities, it was clear that the national authorities were not in a position to provide the applicant with adequate security. He would therefore be exposed to a risk of serious harm in the event of removal to Nigeria and therefore should qualify for subsidiary protection.

[1] Directive 2004/83/EC on minimum standards for the qualification and status of third country nationals or stateless persons as refugees or as persons who otherwise need international protection and the content of the protection granted [2004] OJ L 304/12 (Qualification Directive), art 4(3)(a).

[2] Case C-465/07 Meki Elgafaji and Noor Elgafaji v Staatssecretaris van Justitie EU:C:2009:94.

[3] Case C-285/12 Aboubacar Diakité v Commissaire général aux réfugiés et aux apatrides EU:C:2014:39.

[SC1]This is what I understand from the report?

Art 18 - Right to asylum

The Court does not mention the Charter of Fundamental Rights explicitly but instead cites relevant CofJ caselaw (Elgafaji and Diakite) and the provisions of the Qualification Directive. The Court does refer to Articles 2 and 3 ECHR

- Articles 2 ECHR - Right to life

- Articles 3 ECHR - Prohibition of torture

The interpretation followed by the Italian Supreme Court and the CJEU differs partially from the position of the ECtHR articulated in F.G. v. Sweden where the Strasbourg Court states that “in relation to asylum claims based on a well-known general risk, when information about such a risk is freely ascertainable from a wide number of sources, the obligations incumbent on the States under Articles 2 and 3 of the Convention in expulsion cases entail that the authorities carry out an assessment of that risk of their own motion (see, for example, Hirsi Jamaa and Others v. Italy [GC], cited above, §§ 131-133, and M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece [GC], cited above, § 366). By contrast, in relation to asylum claims based on an individual risk, it must be for the person seeking asylum to rely on and to substantiate such a risk”.[1] In relation to the burden of proof, the ECtHR holds a broad “principle of information”, while the CJEU and the Italian Supreme Court states that “facts” have to be adduced by the applicant, although it should be noted that it remains for the judicial authority make a legal determination in relation to these facts.

Relevant Judicial Dialogue Techniques