Romania, Court of Appeal Bucharest, NGO ACCEPT v the National Council for Combating Discrimination

The NGO ACCEPT claimed in front of the NCCD that A.B.’s statements:

- directly discriminated on the basis of sexual orientation, and

- violated the principle of equality regarding the hiring policy and brought an offense to the dignity of persons having a homosexual orientation.

- fell outside the scope of work relations, as referred to by Art. 5 and 7 of Government Ordinance 137/2000 regarding the prevention and sanctioning of all forms of discrimination (GO 137/2000), but

- fell under the scope of Art. 15 of GO 137/2000, as these represented a behaviour which purpose was to touch upon the human dignity of a certain group of persons or to create a degrading or humiliating environment for them, based on their sexual orientation.

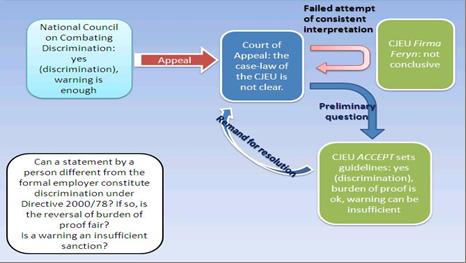

The Court of Appeal, seized of the challenge of this decision, raised a question for a preliminary ruling to the CJEU. The referral court was aware of Firma Feryn precedent, in which CJEU found that a similar discriminatory statement on grounds of race made by an employer constitutes direct discrimination under Art. 2(2) of the Racial Equality Directive (2000/43/EC). However, due to the factual differences of the instant case (A.B. was not formally an employer, and the discriminatory conduct was based on sexual orientation rather than race), the Court of Appeal was not sure whether it would be distinguishable in legal terms from the situation in Firma Feryn. The Court of Appeal therefore asked whether A.B.’s statement could constitute direct discrimination under Art. 2(2) of Equal Employment Directive (2000/78/EC) or, at least, a fact establishing a presumption of discrimination that was for the defendant to rebut. The national court also asked whether shifting the burden of demonstrating the absence of discriminatory policies on the F.C.S. Football Club would yield unfair results, and whether the statutory limitation setting a 6-month period of limitation, after which no fine can be imposed for breach of the national provisions transposing the Directive, frustrates the correct enforcement of the rights protected therein.

The CJEU delivered the preliminary ruling in the ACCEPT case (Case C?81/12) on 25 April 2013. The CJEU confirmed at the outset that it is only for the national court to make the finding on the alleged discrimination, without prejudice to the CJEU’s power to provide national courts with helpful guidelines on how to reach such finding. On the questions raised by the Court of Appeal, CJEU held the following:

- Discriminatory statements from a person not formally related to the F.C.S. Football Club

- Reverse burden of proof – prima facie evidence (statement) - probatio diabolica

- Proportionate, effective and dissuasive sanction

Through the use of preliminary questions the national court wants to understand the exact scope of previous CJEU’s judgments with respect to equivalent, but not identical, facts and EU non-discrimination norms. The national court also questions the allocation of the burden of proof in discriminatory conduct cases, inviting the CJEU to narrow down the scope of application.

- Case C-54/07 Firma Feryn NV (2008)

First, the Court of Appeal of Bucharest invoked Firma Feryn case, notably paragraph 19 thereof, to clarify the scope of Article 267 TFEU provisions.

Second, Firma Feryn case is used as justification for the necessity of a preliminary reference and in support of the admissibility of referral. The referring court asked the CJEU whether the interpretation CJEU gave to Art. 8(2) of the Racial Equality Directive in Firma Feryn can be applied by analogy to Art. 10 of the Equal Employment Directive. In concreto, the Court of Appeal asks if discriminatory statements could create a presumption of discriminatory employment policy of the Football Club. The Court of Appeal disagreed with the respondent’s claim that the preliminary questions were fact-specific and did not raise a question of interpretation of the EU norm of general interest. After citing the exact content of para. 19 of Firma Feryn, the referring court stated that: “Formulating the preliminary questions in concrete terms does not have the significance of requesting the application of EU norms to a particular case, but is meant to provide necessary information to the European Court so that its interpretation will be useful to the national court. Formulating the preliminary questions in imprecise terms could well lead to provide an answer too general and that cannot be used by the national court for solving the case.”

- Case C- 415/93 Bosman and Case Firma Feryn NV

The referring court cited the two judgments as the most relevant CJEU jurisprudence to indicate on the interpretation of EU norms to the specific circumstances of the case before it. However, the referring court found that the facts of the present case were different from those of the Bosman and Firma Feryn. Namely, the author of the discriminatory statements, A.B., could not be considered an employer under the Equal Employment Directive, as he was no longer a shareholder of the Football Club. Therefore, the referring court appreciated that the existing CJEU jurisprudence did not fully clarify the interpretation of EU norms in regard to the specific circumstances of the case at hand: “[t]he invoked jurisprudence is not enough for the national court to clarify the exact scope of the notion of direct discrimination in labour given that discriminatory statements coming from a person who, by law, cannot bind the company that is recruiting staff but, due to the close relationships it has with the company, could decisively influence its decision or, at least, could be perceived as a person who can decisively influence the decision.” […]

-

The Court of Appeal raised a preliminary question to obtain from the CJEU reassurance that the principles laid down in the EU law and CJEU jurisprudence would hold in the circumstances of the instant case

The Bucharest Court of Appeal was convinced that Firma Feryn NV interpretation of Art. 2(2)(a) of Racial Equality Directive (2000/43/EC) would hold true also with Art. 2(2) of Equal Employment Directive (2000/78/EC). Consequently, public declarations accounting for the discriminatory hiring policies of an employer constitute direct discrimination, even if a victim is not identifiable. However, the national court decided to leave no space for doubts. To this end, the court included in its preliminary question the full transcription of Mr. A.B.’s statement, to allow for the CJEU’s exact review of its discriminatory elements. The national court was convinced that the correct interpretation of the Government Ordinance transposing the Equal Employment Directive 2000/78 needed to adhere to the judgments of Bosman (C-415/93) and Firma Feryn, but raised a preliminary question to obtain the answer of CJEU with regards to the circumstances of the instant case. - CJEU deferred the necessary findings to the national court

The CJEU was cautious in its ruling. It confirmed that discriminatory statements can be attributed to an employer even in a situation akin to the one in the main proceedings, but deferred the necessary findings to the national court. As such, CJEU held that it was for the national court to assess on the relevance of the evidentiary burdens are discharged by the parties and the appropriateness of the national law remedies. - The Court of Appeal advanced a genuine doubt as to whether the interpretation of Art.8 of the Racial Equality Directive on the reversed burden of proof (as provided in Firma Feryn) could extend to the equivalent provision of Directive 2000/78.

Art. 8 of Directive 2000/43, like Art. 10 of Directive 2000/78, provides for a reversed burden of proof in case of presumption of discrimination. In Firma Feryn the CJEU had concluded that public statements by the employer confirming its unwillingness to hire employees from a specific group would qualify as facts giving rise to such presumption.

The Court of Appeal reasoned that this approach would impose a burden that is impossible to discharge on the defendant (probatio diabolica). In the view of the national court, the only possible way to rebut such presumption, would be to show that a homosexual player was hired. This, besides being unreasonable, is in itself problematic as it implicates that the employer is aware of, and looking into their players’ private life.

The CJEU finally clarified how to circumvent this dilemma: the defendant proof consisting in refutation of a prima facie discrimination must not necessarily consist in the demonstration that a gay player was signed or considered for hiring. The act of the Football Club of immediately distancing itself from A.B's statement would have constituted a sufficient proof. The CJEU suggested to the national court that a consistent interpretation of the domestic legislation with the wording and purpose of Directive 2000/78, would render the time-limit for the imposition of a fine inapplicable. - Balance of rights: freedom of expression and right to private life. Croatian case - Zdravko Mamic.

Unlike the Croatian case (Zdravko Mamic), the Court of Appeal has not made any reference to the principle of freedom of expression for the benefit of the defendant, or the issue of the private life of the alleged discriminated football player. The ECHR, or constitutional rights were not raised.

Relevant Judicial Dialogue Techniques